The name of the person in whose honor the American continent was named is known to everyone. This is the Spanish conqueror of the sea Amerigo Vespucci, an associate of Columbus and the discoverer of dozens of islands. Although many wonder why he has a whole continent, and Columbus, who was not just standing next to him, is only one country, and not the largest?

Who is responsible for this decision? Let's find out.

The version from our school textbooks says: Vespucci was an adventurer and a crook who, out of selfish intentions, tried to take glory away from the great Columbus.

But who named the continent America?

The name of this man is perfectly known: his name is Martin Waldseemüller, he comes from Germany, was born 540 years ago and lived only forty years. He was not a professional traveler, a pioneer in the service of some crown - just the son of a small shopkeeper from one of the south German cities, who studied at the university and became a professor of cartography and cosmology. In 1507, together with his friend Mathias Rignman, he published a map of the world on twelve wooden sheets and a sticker map for a globe. All this was provided with a detailed and thorough commentary in Latin. The map was made according to the petal model and was intended for a wooden globe.

The basis for his research were the works of the ancient Greek, the great scientist and naturalist Ptolemy, in particular the eight-volume "Guide to Geography", as well as vespucci's diaries and his correspondence with the Duke of Lorraine René II, the patron of geography. Out of respect for his sources, the author placed their portraits on the cartouche of the world map developed by him.

But America did not get its name out of gratitude. The original idea was to place "terra nullis" or "terra incognita" on the map, as almost everyone did in those days. But the master cartographer was convinced of the correctness of Vespucci, who believed that it was about the discovery of a new continent, and not Columbus, who considered all the open lands to be part of Asia, or rather, India, the shores of which he managed to reach, using the western route instead of the eastern one.

The feminine name of the continent

Thus, it seemed self-evident to the German cartographer that the newly discovered land should be given the name Vespucci, not thomas of the unbelieving Columbus, for whom the newly discovered lands remained part of India or Japan.

The form of the word was determined by the toponymic tradition: all continents were called by female names, the same was laid to the newly discovered land in the distant West, beyond the Atlantic. So america was made out of Amerigo.

The Seed of Doubt

The maps were published in thousands of copies in 1507: financial support for the project was provided by the ruler of Lorraine, Duke René. He also contributed to the dissemination of new ideas of geographical science, sending the works of his protégé to European royal courts, merchant companies and corporations, as well as patrons of the arts, travelers and university libraries.

Thus, the term came into circulation very quickly and became commonplace.

At the end of his days, the cartographer even doubted that Vespucci had made the discovery of a new continent, because his diaries, which in fact were written by a completely different person, and Vespucci was only appropriated and published, hid many contradictory moments, and some stories looked unreliable. Perhaps for this reason, Waldseemüller in later versions of the map began to use the traditional version of "terra incognita" instead of "America", but it was impossible to change anything in this regard.

And when the author died, the republication of his maps and atlases completed the triumph of Vespucci, despite the fact that the name of the cartographer was densely and very long forgotten by the scientific community. Only in the 60s of the XIX century, the geographer, naturalist, scientist and passionate traveler Alexander von Humboldt, filled with pride in his fellow tribesman and countryman, wrote an article about him in one of the popular scientific journals of that time.

For many years, the original map on which the name "America" was mentioned for the first time – from the same series of a thousand pieces – was considered lost, until, finally, in 1901, a complete set of a dozen sheets was discovered in the library of Wolfhegg Castle. The owner, Duke Johann zu Waldburg-Wolfhegg, twenty years ago sold the find to the U.S. government and the Library of Congress for $10,000,000 , the record amount ever paid for the card. At the same time, the deal could not take place in principle, since American experts had doubts about the authenticity, and the German authorities could not agree with the sale of such a valuable historical relic, so special permission was required. He was extradited only because the administration of the German Chancellor did not dare to spoil relations with its American partners.

Originals and fakes

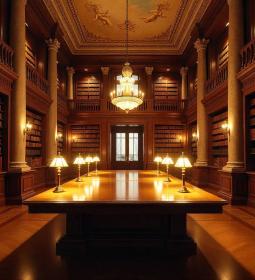

At the moment, the original version of the same map is exhibited in a special hall of the Washington Library of Congress, behind armored glass, and a special microclimate has been created inside the showcase that slows down the process of oxidation of paper. It is understandable: for Americans, not only US citizens, this is a kind of relic, an analogue of a birth certificate or a record "with entry in a personal file" (although in fairness it should be noted: Waldseemuller drew on his maps the central and southern part of the continent - the northernmost object that got there was a fragment of east Florida).

What is interesting: the map has been preserved in one copy, but as many as four sets for assembling a globe from petals from a cosmographic set of 1507 have survived to the present time.

One map is kept in the library of the University of Munich and is occasionally exhibited in the main hall. Another , however, fake, as it turned out - from the widow of a famous antiques dealer was purchased by the library of Bavaria. The counterfeit was detected thanks to the chemical analysis of printing ink, in which microparticles of iron and titanium were found, which began to be used in printing books only in the 80s of the XIX century - before that, the paint did not include iron in its composition. Two more are kept in private collections.